Same scene of Arras, France in 2016 on Google Streetview

The source of the material from which this journal has been compiled is a small pocket diary in which brief entries were made daily throughout the writer’s short spell on active service in the British Army in 1917. The events and incidents, both trivial and tragic, and the names of those who shared in the writer's experiences are authentic.

30th June 1917

29th June 1917

28th June 1917

From 7am the usual round of P.T., bayonet work on the sacks and ‘bombing’ continued for five hours without a break. The throwing of hand grenades was a cunningly planned exercise guaranteed to provide the necessary incentive to maximise effort. Two teams faced each other at a carefully judged distance of thirty yards. At the word of command everyone let fly at their opposite numbers. There were no rules to the game and thereafter it was every man for himself. The heavy missiles flew through the air at all angles. Self-preservation demanded a quick eye and fleetness of foot and a fighting spirit. Fortunately the grenades were not live otherwise the damage to personnel would have been great, as it was we thoroughly enjoyed it.

In front of the ruins of the Town Hall of Achicourt the Battalion , dressed in clean fatigue, was drawn up on parade. Spit and polish was called for and the presence in the Square of the large Foden Steam Wagon, together with several ancillary boilers on wheels had the troops puzzled until, with one accord, they were ordered to strip – ‘Operation De-louse’ had commenced. In happier times the sight of several hundred bodies lined up in a complete state of nature would have been a fantastic spectacle for the worthy citizens of their ancient and, no doubt, dignified town but they had long since departed and we, if not they, were spared much embarrassment.

Every stitch of clothing was removed and each bundle tied with string to which were attached our identity discs. The bundles were then thrown into the steam chambers and, cold and miserable, we waited interminably for the Army Launderette to discharge our particular consignment. However it was all in a good cause and we consoled ourselves with the prospect of being clean and wholesome once again. We opened our bundles joyfully anticipating the sight of massive slaughter. The treatment must have been intense for the moulded black buttons on crumpled uniform jackets had not only lost all trace of the regimental crest but were misshapen lumps of ebonite. The coarse woollen vest and pants were examined but there were no corpses. The families which had attended on us for their food and lodging over the past months were still with us, a little excited perhaps and hungry, otherwise they appeared as happy as Larry and thereafter continued to thrive.

7am physical, musketry, etc.

Bombing - 30 yards.

Afternoon, clothes fumigated by Foden tractor.

In front of the ruins of the Town Hall of Achicourt the Battalion , dressed in clean fatigue, was drawn up on parade. Spit and polish was called for and the presence in the Square of the large Foden Steam Wagon, together with several ancillary boilers on wheels had the troops puzzled until, with one accord, they were ordered to strip – ‘Operation De-louse’ had commenced. In happier times the sight of several hundred bodies lined up in a complete state of nature would have been a fantastic spectacle for the worthy citizens of their ancient and, no doubt, dignified town but they had long since departed and we, if not they, were spared much embarrassment.

Every stitch of clothing was removed and each bundle tied with string to which were attached our identity discs. The bundles were then thrown into the steam chambers and, cold and miserable, we waited interminably for the Army Launderette to discharge our particular consignment. However it was all in a good cause and we consoled ourselves with the prospect of being clean and wholesome once again. We opened our bundles joyfully anticipating the sight of massive slaughter. The treatment must have been intense for the moulded black buttons on crumpled uniform jackets had not only lost all trace of the regimental crest but were misshapen lumps of ebonite. The coarse woollen vest and pants were examined but there were no corpses. The families which had attended on us for their food and lodging over the past months were still with us, a little excited perhaps and hungry, otherwise they appeared as happy as Larry and thereafter continued to thrive.

7am physical, musketry, etc.

Bombing - 30 yards.

Afternoon, clothes fumigated by Foden tractor.

|

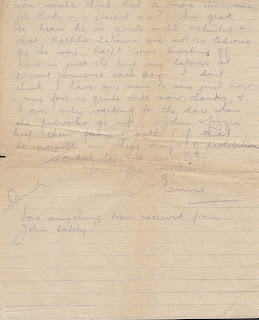

| Original diary entry |

|

| Original journal notes |

26th June 1917

The evening was dry and a session on the range was welcomed by the snipers of B Company but not by the markers assigned for duty fiddling with paste pot and little pieces of paper whilst others had the fun of an attractive pastime. The exercise became even more arduous when the Lewis Gun team held a practice shoot because there was always the chance of ricochets. The weather being fine the Officers of B Company strolled up to watch and also to pop off a few shots with their Webleys.

At the end of our shoot the markers were relieved of their duties and the snipers moved down to the butts, a degrading duty we thought for specialists of our calibre but the man on the next target to mine was quite pleased with the opportunity unexpectedly presented. He was a truculent individual and it was apparent that his rebellious attitude to Army discipline had not gone unnoticed in the past. The Officers produced their Webleys and a running commentary by my friend on the right went somewhat as follows. “Who’s this – it’s that old bastard X, got an ‘inner’ has he – I’ll give him an ‘outer’. Here comes Lieutenant Y – first one an ‘outer’ - nice fellow Lieutenant Y – I’ll give him a ‘bull’ – no, mustn’t overdo it – give him an ‘inner’.” ‘Rebellious’ continued in the same strain for all his customers and at the finish he was eminently satisfied having blasted several reputations in the Mess and provided a minor boost to the morale of the less competent.

7am physical fatigue dismantling German wire.

On range. 32 points. 2 - 6pm.

At the end of our shoot the markers were relieved of their duties and the snipers moved down to the butts, a degrading duty we thought for specialists of our calibre but the man on the next target to mine was quite pleased with the opportunity unexpectedly presented. He was a truculent individual and it was apparent that his rebellious attitude to Army discipline had not gone unnoticed in the past. The Officers produced their Webleys and a running commentary by my friend on the right went somewhat as follows. “Who’s this – it’s that old bastard X, got an ‘inner’ has he – I’ll give him an ‘outer’. Here comes Lieutenant Y – first one an ‘outer’ - nice fellow Lieutenant Y – I’ll give him a ‘bull’ – no, mustn’t overdo it – give him an ‘inner’.” ‘Rebellious’ continued in the same strain for all his customers and at the finish he was eminently satisfied having blasted several reputations in the Mess and provided a minor boost to the morale of the less competent.

7am physical fatigue dismantling German wire.

On range. 32 points. 2 - 6pm.

|

| Original diary entry |

|

| Original journal notes |

25th June 1917

24th June 1917 (Sunday)

The Battalion was now completely ‘at rest’. Not even Church Parade with its inevitable regimentation. Unfortunately the day was spoilt for me when detailed as mess orderly. A duty all detested, although if the cooks were in a good mood it had its compensations. The worst part of cookhouse fatigue was the cleansing of innumerable pots, bins and other utensils without the aid of either hot water or cleansing materials. Gritty earth and newspaper had to suffice for the removal of half an inch of cold, solid grease and the Sergeant expected miracles. The only bright spot of the day was cheerful music played on the bayonet course by the Divisional Band from 2 until 4:30 pm.

Mess orderly.

No church parade.

Divisional Band 2-4:30pm. "The Broken Doll" (1)

(1) 'A Broken Doll' - a song popular during World War 1. Written by Clifford Harris and composed by Jas W. Tate. 1916.

Mess orderly.

No church parade.

Divisional Band 2-4:30pm. "The Broken Doll" (1)

|

| Original diary entry |

|

| Original journal notes |

(1) 'A Broken Doll' - a song popular during World War 1. Written by Clifford Harris and composed by Jas W. Tate. 1916.

23rd June 1917

We were now due for a quiet spell away from the line. The half trained men who filled the gap after the slaughter of Easter Monday were good enough to man the trenches in the Arras sector during the lull after the storm. Apart from casual parades for inspection, a bath of sorts and the issue of clean underwear, the only event of any importance was the arrival of a fresh draft from Redhill. I was glad to welcome many old friends from D Company including rotund and jovial Tolliday who, alas, failed to make the return journey.

Rifle inspection and bath and change.

New draft joins.

Tolliday and Murphy of D Company (Redhill).

Rifle inspection and bath and change.

New draft joins.

Tolliday and Murphy of D Company (Redhill).

|

| Original diary entry |

|

| Original journal notes |

22nd June 1917

Morning came and the problem of the puttees was quickly solved by winding them on inside out. If the M.O. had been present he would probably have diagnosed elephantiasis but to the casual observer I had the cleanest pair of puttees on parade. Unfortunately the R.S.M. himself decided to take the parade that morning and ‘Spiky’ with the waxed moustaches was a fearsome being to the lowly rifleman. He, with Sergeant Partridge in attendance, passed slowly along the ranks – “Do that button up” – “Take that muck out of your pocket” – “Put your belly in” – and similar remarks dear to the hearts of all sergeant majors. At last he was level with me – a quick glance up and down, a slight hesitation and the great man himself bent down and quickly turned down one fold of a puttee. He said exactly what one would expect. For some unaccountable reason Sergeant Partridge found difficulty with his notebook and by the time his pencil was poised the R.S.M. had moved on several yards. In a quiet voice ‘Birdie’ spoke, “I know your name, you’re Polkinghorne" and hastily scribbled something in his book. Needless to say the mythical Polkinghorne never appeared on a charge but he spent the rest of the day removing all traces of mud from his person.

Rifle inspection - and kit inspection.

Pay day.

Afternoon sleep.

Rifle inspection - and kit inspection.

Pay day.

Afternoon sleep.

|

| Original diary entry |

| Original journal notes |

21st June 1917

Not until 9am on the morning of the 21st did we reach the ruins of Achicourt, formerly a small town a mile or so to the west of Arras. It was here we were told that the QWR had suffered heavy casualties when a surprise bombardment during the battle of Arras reduced the whole side to a shambles. The Battalion losses were particularly heavy in the Town Hall and a QWR cemetery was sited outside the town. Apart from the rifle and kit inspection there were no parades but we all attended a memorial service at a French Protestant church.

Kit inspection was the usual pantomime as performed, no doubt, by the British soldier throughout the ages and we have it on good authority that the time honoured practice still exists. In two ranks facing, each man displayed his kit on the ground before him whilst the platoon commander with NCO in attendance gave individual attention to the articles set out for inspection. Since few men could produce their full quota of army issue, especially after a spell in the line, it was necessary to employ a little ingenuity if beer money was not to be wasted in making up discrepancies. At the commencement of operations frantic signals passed from one rank to the other after which socks, brushes, cutlery and other miscellaneous articles flew through the air to the other side. On the return journey of the inspecting officer down the other rank the borrowed articles were returned in like manner, together with any additional articles requested by sign language. The whole blatant exercise was carried out with much joyous abandon. It seemed impossible that the inspecting officer and NCO were not aware of the farce being performed under their very noses. There can only be one possible explanation.

8th Battalion was billeted in the ruins of an estaminet open to the sky which on the day was gloomy and depressing. On dismissal for the day our final injunction was to get “cleaned up”. I tackled the job with little enthusiasm. By the time rifle and sword were cleaned, boots dubbined and the assorted lumps of chalk from the Arras trenches, together with candle ends and other miscellaneous treasures, removed from the box respirator it was time to turn my attention to my puttees which were in a sorry state. Those night excursions to the river for water had resulted in a layer of dried mud a quarter of an inch thick and hard as iron. By this time the rest of my billet companions had given up their labours and were stretched out for the night on the hard stone floor. I quickly followed their example.

Arrived early morning Achicourt.

Rifle inspection only.

Service in French Protestant Church ruins.

Google Maps entry for Achicourt here

Kit inspection was the usual pantomime as performed, no doubt, by the British soldier throughout the ages and we have it on good authority that the time honoured practice still exists. In two ranks facing, each man displayed his kit on the ground before him whilst the platoon commander with NCO in attendance gave individual attention to the articles set out for inspection. Since few men could produce their full quota of army issue, especially after a spell in the line, it was necessary to employ a little ingenuity if beer money was not to be wasted in making up discrepancies. At the commencement of operations frantic signals passed from one rank to the other after which socks, brushes, cutlery and other miscellaneous articles flew through the air to the other side. On the return journey of the inspecting officer down the other rank the borrowed articles were returned in like manner, together with any additional articles requested by sign language. The whole blatant exercise was carried out with much joyous abandon. It seemed impossible that the inspecting officer and NCO were not aware of the farce being performed under their very noses. There can only be one possible explanation.

8th Battalion was billeted in the ruins of an estaminet open to the sky which on the day was gloomy and depressing. On dismissal for the day our final injunction was to get “cleaned up”. I tackled the job with little enthusiasm. By the time rifle and sword were cleaned, boots dubbined and the assorted lumps of chalk from the Arras trenches, together with candle ends and other miscellaneous treasures, removed from the box respirator it was time to turn my attention to my puttees which were in a sorry state. Those night excursions to the river for water had resulted in a layer of dried mud a quarter of an inch thick and hard as iron. By this time the rest of my billet companions had given up their labours and were stretched out for the night on the hard stone floor. I quickly followed their example.

Arrived early morning Achicourt.

Rifle inspection only.

Service in French Protestant Church ruins.

|

| Original diary entry |

|

| Original journal notes |

20th June 1917

The day was quiet and as soon as darkness fell the QWRs were relieved by the Rangers and the London Scottish.

The whole of the area being a maze of deep trenches the way back was complicated and tiring. In single file we negotiated the contours of the communication trenches by walking along the parapets and parades, occasionally crossing over the six-foot drop between in order to cut off corners. Suddenly my foot caught in a section of telephone wires and I pitched headlong into a deep trench. I was not badly hurt but two nasty gashes were bleeding on forearm and hip. Cuts and wounds were a matter of daily occurrence, especially when handling the masses of German barbed wire which still created pitfalls for the unwary. No doubt we had to thank the abominable A.T. injections by RAMC for the fact that such untended mutilations of the flesh healed without any sign of festering.

We plodded on for hours but the awaited road in the back area, which would take us to food, rest and sleep, failed to materialise. B Company, Lieutenant May in command, was lost!

Fairly quiet.

Relieved at night by the Rangers and Scottish.

Back to Achicourt. Billet. Ruins of estaminet.

The whole of the area being a maze of deep trenches the way back was complicated and tiring. In single file we negotiated the contours of the communication trenches by walking along the parapets and parades, occasionally crossing over the six-foot drop between in order to cut off corners. Suddenly my foot caught in a section of telephone wires and I pitched headlong into a deep trench. I was not badly hurt but two nasty gashes were bleeding on forearm and hip. Cuts and wounds were a matter of daily occurrence, especially when handling the masses of German barbed wire which still created pitfalls for the unwary. No doubt we had to thank the abominable A.T. injections by RAMC for the fact that such untended mutilations of the flesh healed without any sign of festering.

We plodded on for hours but the awaited road in the back area, which would take us to food, rest and sleep, failed to materialise. B Company, Lieutenant May in command, was lost!

Fairly quiet.

Relieved at night by the Rangers and Scottish.

Back to Achicourt. Billet. Ruins of estaminet.

|

| Original diary entry |

|

| Original journal notes |

19th June 1917

The rains persisted but apart from the usual 9am strafe the Hun was content to send over the occasional salvo during the rest of the day. At dusk the company resumed its labours with pick and shovel in no mans land. The light in the western sky was still sufficient for the NCO to keep our labours going. I was busy, spade in hand, when a series of strange ‘plops’ sounded nearby. On turning to seek enlightenment from my companions not one was to be seen and I was alone in the wilderness until one after another they slowly rose from the ground. Thirty-four little ‘plops’ were, in fact, caused by a shower of rifle grenades with their steel rods sticking up like a fence surrounding me. Fortunately they failed to explode. I seemed we were not invisible from the German lines since a few minutes later several shells of 5.9 calibre exploded in the middle of the working party causing eight minor casualties. Willis, who was shovelling the products of my pick, received a splinter in the neck and Coombe a slight wound in the leg. Stretcher bearers appeared at the double and the casualties, most of whom were quite capable of walking back to the dressing station, were carted away at top speed. This was textbook warfare, neat and tidy, and reminiscent of those thrilling battles which, with the help of Mr Brittain’s magnificent redecorated lead soldiers, my brother and I used to play on the kitchen table in the days when Queen Victoria was on the throne.

We were not unduly worried by the casualties but the sequel several minutes later really had us bothered. Young C-----, normally a cheerful little cockney, had evidently brooded on the incident. Suddenly losing his self-control he jumped into the air shouting “Mother” and dashed off to the rear as fast as his little legs could carry him. Several men attempted to restrain him but he was too quick and disappeared in the gathering mist. The incident was probably nothing new to the NCO in charge of the party and his remark was simply, “Let him go, he’ll be back”. The truant was not in the trench when we returned from our labours. Desertion in the face of the enemy was a crime which we understood could attract the supreme penalty and our concern for the popular little cockney was great. In the afternoon of the following day he sheepishly returned to the fold. We youngsters were always conscious of the sympathy and understanding displayed by the pre-war Territorial NCOs and once again we were not disillusioned. “C-----, if you do that again I will kick your backside so hard you won’t dare sit down for weeks – get back to your post”. The incident was finished and thereafter young C----- kept his two feet on the ground and eventually received the honourable scars of battle.

Wet and stormy.

Digging on the front line trench.

Two shells over. Willis (2 yards away) and Coombe wounded.

Six casualties.

Also rifle grenades over.

We were not unduly worried by the casualties but the sequel several minutes later really had us bothered. Young C-----, normally a cheerful little cockney, had evidently brooded on the incident. Suddenly losing his self-control he jumped into the air shouting “Mother” and dashed off to the rear as fast as his little legs could carry him. Several men attempted to restrain him but he was too quick and disappeared in the gathering mist. The incident was probably nothing new to the NCO in charge of the party and his remark was simply, “Let him go, he’ll be back”. The truant was not in the trench when we returned from our labours. Desertion in the face of the enemy was a crime which we understood could attract the supreme penalty and our concern for the popular little cockney was great. In the afternoon of the following day he sheepishly returned to the fold. We youngsters were always conscious of the sympathy and understanding displayed by the pre-war Territorial NCOs and once again we were not disillusioned. “C-----, if you do that again I will kick your backside so hard you won’t dare sit down for weeks – get back to your post”. The incident was finished and thereafter young C----- kept his two feet on the ground and eventually received the honourable scars of battle.

Wet and stormy.

Digging on the front line trench.

Two shells over. Willis (2 yards away) and Coombe wounded.

Six casualties.

Also rifle grenades over.

|

| Original diary entry |

|

| Original journal notes |

18th June 1917

The day broke wet and stormy. Bivvies gave but little protection from the unending torrents and the glamour of those first few days in the line was no more. The sodden chalky trenches became treacherous underfoot. Burdened with picks and shovels the nightly stint was the construction of a new trench some yards ahead of the front line position. The results were meagre and unrewarding but nobody seemed to mind.

Wet and stormy - otherwise quiet.

Trench digging in advance of front line.

Mr Smith leaves for the RFC.

Wet and stormy - otherwise quiet.

Trench digging in advance of front line.

Mr Smith leaves for the RFC.

|

| Original diary entry |

|

| Original journal notes |

17th June 1917 (Sunday)

The comparative freedom of movement during the daylight hours invited liberties and Bradley and I soon found ourselves crossing the sunken road dividing the vast trench system from the rubble and masonry which had once been the village of Wancourt. The devastation was not equal to the shambles of Beaurain and here and there remnants of buildings had survived the enemy guns. Poppies abounded in the region but one hardly expected to see roses shining in Picardy. On the far side of the road there was a garden encircled by a low brick wall surmounted by high iron railings. A tall wrought iron gate gave entrance to what must have been the carefully tended rose garden of a house of some distinction. The house, alas, was no more but the roses still flourished in colourful abandon.

Our main occupation was, however, to satisfy the urge to pour water down our parched throats and we were lucky. Along the road a crowd of men from various units of the Brigade were milling around an ancient pump from which gushed a never-ending stream of water. We filled our bottles and beat a hasty retreat before authority came upon the scene.

Night brought the usual wire carrying fatigue with a modicum of indiscriminate shelling from the other side, but the Company returned unscathed.

Buckshee water from Wancourt (Demolished).

Wire carrying.

Fritz shells us.

Our main occupation was, however, to satisfy the urge to pour water down our parched throats and we were lucky. Along the road a crowd of men from various units of the Brigade were milling around an ancient pump from which gushed a never-ending stream of water. We filled our bottles and beat a hasty retreat before authority came upon the scene.

Night brought the usual wire carrying fatigue with a modicum of indiscriminate shelling from the other side, but the Company returned unscathed.

Buckshee water from Wancourt (Demolished).

Wire carrying.

Fritz shells us.

|

| Original diary entry |

|

| Original journal notes |

16th June 1917

The day passed quietly. In the reserve trenches there was ample opportunity to survey and actually investigate the immediate surroundings. Every ration fatigue was a welcome break since the rendezvous with the supply column brought one to the outskirts of the ruins of Wancourt where the Battalion suffered grievous losses during the Easter fighting. The nights fatigue entailed the manhandling through the narrow and winding trenches, at the cost of considerable laceration of the flesh, those cumbersome contraptions of heavy timber and barbed wire known as ‘knife rests’. These were dumped in the shellholes of no mans land with the pious hope that one day Jerry might encounter them under less favourable conditions.

Move to Reserve trenches - "Buzzards".

Bivvy shared with Bradley.

Night work carrying wire to the front line.

Ration fatigue.

Move to Reserve trenches - "Buzzards".

Bivvy shared with Bradley.

Night work carrying wire to the front line.

Ration fatigue.

|

| Original diary entry |

|

| Original journal notes |

15th June 1917

At 9am the Hun commenced his regular morning strafe on the support lines and the heavy shells bursting either side of the trench evidenced the accuracy of his gunnery. We anxiously awaited the direct hit which seemed inevitable, at the same time not oblivious to the possibility of an attack following the long, intensive bombardment.

Suddenly the racket stopped and from our crouching position we rose up to the alert. At once our NCO dashed up shouting “first six men, this way – quick as hell”. Grabbing rifles and swords we ran, anticipating we knew not what. The NCO said “Put those bloody rifles down, you won’t need them”. After some ten or fifteen yards our progress was barred. Straddling the trench was an enormous mound of huge boulders of solid chalk. The shell which had caused the damage had burst some yards in front of the parapet splitting a seam in the iron hard ground so that the trench collapsed. Ten or twelve feet below that mountainous heap of chalk one of our company was known to be in his bivvy and a second man was missing. Throughout the rest of the day relays of men laboured with pick and shovel in the boiling sun until by evening the crushed and broken body of young Watson was discovered. The other man, whose name I have forgotten, was alive but was said to have been blinded.

In due course our spell in the line was over and we were back in billets. Naturally letters and parcels from home were our first concern. In a corner of the barn stood a massive tea chest addressed to Rifleman Watson. In private life Watson had been employed by a large grocery firm and they had generously despatched to him that enormous crate of comestibles which by wartime standards were luxuries indeed. Why the army accepted such a huge consignment for delivery to the front intrigued us. In accordance with custom the platoon had no compunction in sharing out the contents. Our susceptibility to the tragedy of war was already becoming blunted.

During the night B Company was fully engaged in the wearisome task of erecting more barbed wire entanglements by the tributaries of the Scarfe and before the dawn various companies were moved to exchanged positions. B Company now found itself located in Buzzard Trench in the reserve line. This was an improvement in many respects to the support position although the night trips to the front line, laden with all the paraphernalia of war, were longer and more exhausting.

It was during this spell that an unusually solemn Bradley paid me a visit. “I’ve been detailed as Gas Guard. What does that mean?” I said, “Fine, you have nothing to do but sit on your bottom all day by the Gas Gong (a shell case suspended on a bracket at the side of the trench) and sniff – you beat the gong with your entrenching tool handle, that’s all”. He replied, “That’s alright but I can’t smell!” Pointing to a small red mark on the bridge of his nose he explained that ever since a fall off a bike when he was a schoolboy his sense of smell had been non-existent. He was very sensitive about this and I promised to respect his confidence and also act as his ‘nose’ during his spell on duty. Actually I had been fully aware of his disability for some time but as he took such pride in his physical wellbeing I had kept the knowledge to myself.

During the trips we made together whilst guiding the Queen Vics wiring parties to the front line it was our custom to rest for a few minutes on the way back to our trench in order to partake of a little refreshment. Invariably Bradley, who, by virtue of his additional years liked to be the leader, would dispose himself happily on the most revolting heap of cadavers, or perhaps the remains of some latrine, to open his bread and jam! Tactfully I usually managed to get him to a less unsavoury spot, although there were not many to be found in that region.

Heavy morning strafe.

Shell over my bivvy.

Willis and Watson buried.

Guide to wiring party.

Wiring by Scarfe.

Suddenly the racket stopped and from our crouching position we rose up to the alert. At once our NCO dashed up shouting “first six men, this way – quick as hell”. Grabbing rifles and swords we ran, anticipating we knew not what. The NCO said “Put those bloody rifles down, you won’t need them”. After some ten or fifteen yards our progress was barred. Straddling the trench was an enormous mound of huge boulders of solid chalk. The shell which had caused the damage had burst some yards in front of the parapet splitting a seam in the iron hard ground so that the trench collapsed. Ten or twelve feet below that mountainous heap of chalk one of our company was known to be in his bivvy and a second man was missing. Throughout the rest of the day relays of men laboured with pick and shovel in the boiling sun until by evening the crushed and broken body of young Watson was discovered. The other man, whose name I have forgotten, was alive but was said to have been blinded.

In due course our spell in the line was over and we were back in billets. Naturally letters and parcels from home were our first concern. In a corner of the barn stood a massive tea chest addressed to Rifleman Watson. In private life Watson had been employed by a large grocery firm and they had generously despatched to him that enormous crate of comestibles which by wartime standards were luxuries indeed. Why the army accepted such a huge consignment for delivery to the front intrigued us. In accordance with custom the platoon had no compunction in sharing out the contents. Our susceptibility to the tragedy of war was already becoming blunted.

During the night B Company was fully engaged in the wearisome task of erecting more barbed wire entanglements by the tributaries of the Scarfe and before the dawn various companies were moved to exchanged positions. B Company now found itself located in Buzzard Trench in the reserve line. This was an improvement in many respects to the support position although the night trips to the front line, laden with all the paraphernalia of war, were longer and more exhausting.

It was during this spell that an unusually solemn Bradley paid me a visit. “I’ve been detailed as Gas Guard. What does that mean?” I said, “Fine, you have nothing to do but sit on your bottom all day by the Gas Gong (a shell case suspended on a bracket at the side of the trench) and sniff – you beat the gong with your entrenching tool handle, that’s all”. He replied, “That’s alright but I can’t smell!” Pointing to a small red mark on the bridge of his nose he explained that ever since a fall off a bike when he was a schoolboy his sense of smell had been non-existent. He was very sensitive about this and I promised to respect his confidence and also act as his ‘nose’ during his spell on duty. Actually I had been fully aware of his disability for some time but as he took such pride in his physical wellbeing I had kept the knowledge to myself.

During the trips we made together whilst guiding the Queen Vics wiring parties to the front line it was our custom to rest for a few minutes on the way back to our trench in order to partake of a little refreshment. Invariably Bradley, who, by virtue of his additional years liked to be the leader, would dispose himself happily on the most revolting heap of cadavers, or perhaps the remains of some latrine, to open his bread and jam! Tactfully I usually managed to get him to a less unsavoury spot, although there were not many to be found in that region.

Heavy morning strafe.

Shell over my bivvy.

Willis and Watson buried.

Guide to wiring party.

Wiring by Scarfe.

|

| Original diary entry |

|

| Original journal notes |

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)